Heeding the call for homemade face-masks,

I find my old sewing-machine

where I parked it, ten years ago,

in the wreckage of a storage shed—

nestled in a basket like a brooding hen,

the heavy plastic bag I’d put over it

shredded by time and rats.

Wearing rubber gloves, I carry my old Kenmore

onto the porch, where I sit in the glorious last light

of the late afternoon

filled with thunder clouds in the north

and lit by a rainbow, closer by.

Under the benediction of that sky,

I clean off the dust and dirt

and cobwebs till the hard plastic

gleams again,

And I remember my emotional connection

to this sewing machine

and the ones that came before.

That first Home Ec class in junior high,

when all the girls were assigned to make an apron.

Afterwards I asked to take a summer course

at the Singer Sewing Machine store,

and made an A-line skirt, learning to align

an army of straight-pins

at right angles to the edges

of the tissue-paper pattern pieces,

affixing them to the fabric—

and how to cut through both with skill.

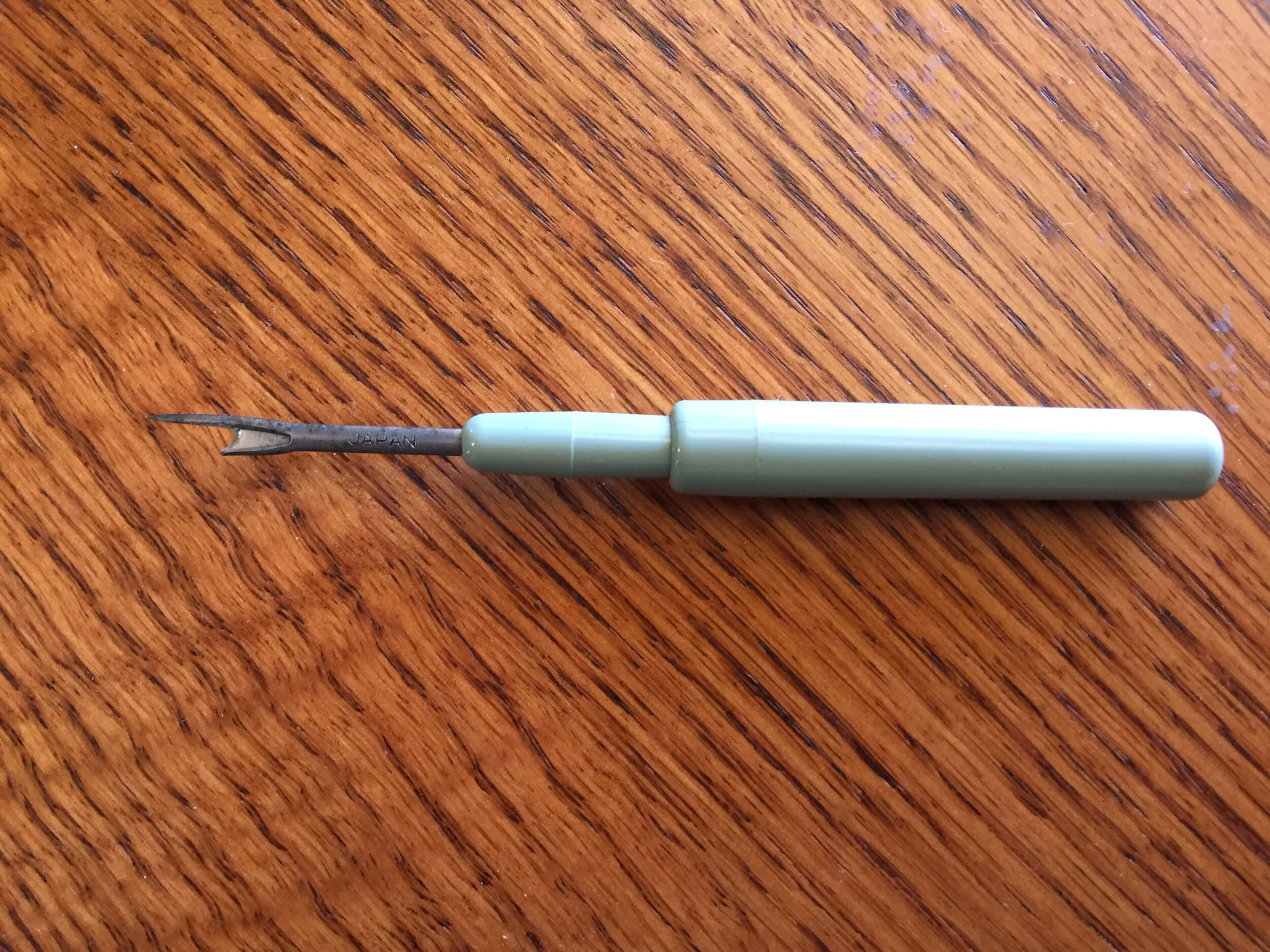

I learned to love a seam-ripper,

with which one can undo

even the most tightly stitched

mistakes.

That first pair of sewing scissors,

which I have still, a gift from my father,

who, before the divorce,

scratched my name into the stainless steel

with calligraphic precision.

I sewed a paisley Nehru shirt for my brother,

and a plain white linen one for his best friend.

A salmon-colored, crisp cotton dress for my mother,

who later requested a sky-blue, square-necked silk blouse

like the one I confected for myself,

with handmade buttonholes edged by a tiny little

blanket-stitch. Was that before or after I’d

called her a bitch and swore that I hated her?

I wish now that I’d held my tongue,

no matter how egregiously

it seemed that she wronged me.

Throughout those lonely teenage years,

I sat long hours at my machine,

raising and lowering the presser-foot,

guiding the fabric underneath it,

the whir of the motor in my ears,

the needle dipping down and down again,

like a derrick drilling for oil.

I tailored a camel-colored, cashmere suit,

fully lined. Interfacing compelled the lapels

to lie flat against my body.

I learned the trick of making

bound buttonholes, every stitch

invisible.

I could see so well close-up then

with my young eyes.

What was the future I imagined for myself

in these clothes, as I sat and sewed?

Sitting before my machine now,

and cleaning off the grime,

I think about the great-grandmother I never knew,

a tailor by profession, in Russia, under the Tsar.

Tailoring skills came to me naturally,

by way of DNA, before I lost them in the swirl

of marriages and motherhood

and trying to make my way

as a writer.

Too poor to buy the fabrics I favored,

or even the patterns for making them—

those Vogue numbers with their oversized envelopes

and elegant designs, each pattern costing as much

as a silk blouse I could find, if I looked hard

and had luck, in a thrift shop or at the Goodwill.

Pregnant with my first and only child,

I felt sure that I would make all his clothes—

and yet there was no time.

Baby-clothes have the lifespan of a butterfly

before one’s child grows out of them.

I became a hunter for consignment clothes,

some of them never used.

I carried my baby in a sling and then a front-pack—

and, later, in a Swedish baby backpack,

all of which I found at those same stores

while I searched for treasures to array us:

silken velvet caps to keep his head warm

during that first winter when he didn’t yet have

any hair. Always on the lookout

for things that were finely made.

For the Halloween parade at his pre-school,

when Julian was almost four,

he told me he wanted to be Butterfly Man,

a super-hero born in his imagination.

I took out my sewing machine

and fashioned a cape

from some diaphanous golden fabric I found

and used an illustrated field-guide to the butterflies

to paint it all over with Monarchs and Swallowtails

and the iridescent blue wings of Morpho Menelaus.

Edged all around with a golden silk cord,

fastened with an antique cloisonné clasp.

With his abundant blond hair, slim silhouette

and olive-green eyes,

he seemed made for his disguise.

I took my sewing machine out again

nearly every Halloween to transform my son

into whomever he wished to be:

One year he was the Pokémon trainer, Ash Ketchum

(known as Satoshi in Japan). Another year,

more labor intensive for me, he was a furry brown bear.

Both the cape and Satoshi’s blue-and-white jacket

hang in the closet where I keep the clothes

I rarely use.

My son is twenty-seven now, a budding engineer

who models the wind in long, elegant equations

that fill whiteboards and hold the promise

to improve the next generation of wind farms,

and make the world a better place. His golden hair

is brown now, and reaches to his waist.

He lives and studies far away, although we speak

at length at least once a week and, lately, more.

Today I wonder, filled with fear,

will we ever see each other again?

I place the butterfly cape over my shoulders,

hoping to unleash a super-hero

lurking inside of me.

Tomorrow, after I’ve done some more research,

I’ll remind myself how to thread the Kenmore—

and get to work.

Copyright © 2020 by Barbara Quick